Posted on July 4, 2017

Creative Portuguese: Learn through speaking

My new publication has arrived! After years working on this method and textbook, it’s finally on sale.

The idea with this method is to make the student learn through conversation, asking and answering to questions in a set of particular verbs that will trigger certain tenses. To date, there is no other book that focuses on conversation like this for learning Portuguese (and probably the same for other languages). Some books that are marketed as ‘conversational’, will only show you phrases about how to order food or how to order a taxi. They only ask you to memorise lines, a very old approach that is not effective at all. The Verb Set Method is about having a real conversation and it’s intended to be used between teacher and student, or student and his/her native language partner (it could be a family member or a What’s App friend).

The concept is, as pointed out in the book’s epigraph:

One learns grammar from language, not language from grammar. (Toussaint-Langenscheidt)

I have been using this method now for a long time with my students. I have never seen so much progress! When students learn through textbooks, they struggle to memorise conjugations tables, which many times they will forget or not use what they have learned. Sometimes students learn how to read through grammar methods, that’s absolutely true. But when it comes to speaking, they lack the confidence and don’t remember things quickly. Through conversational practice, students learn words and expressions they tend to use in their mother tongue and also gain confidence.

So how does it work?

The student looks at the verb set sheet. Then the teacher asks him or her questions. When the student doesn’t know a word, he/she will ask “como se diz…” (how do I say…) and then the teacher will help. This way, the student will learn through speaking. After this round, the student asks the same (or similar) questions to the teacher. This way, the student learns how to ask things as well.

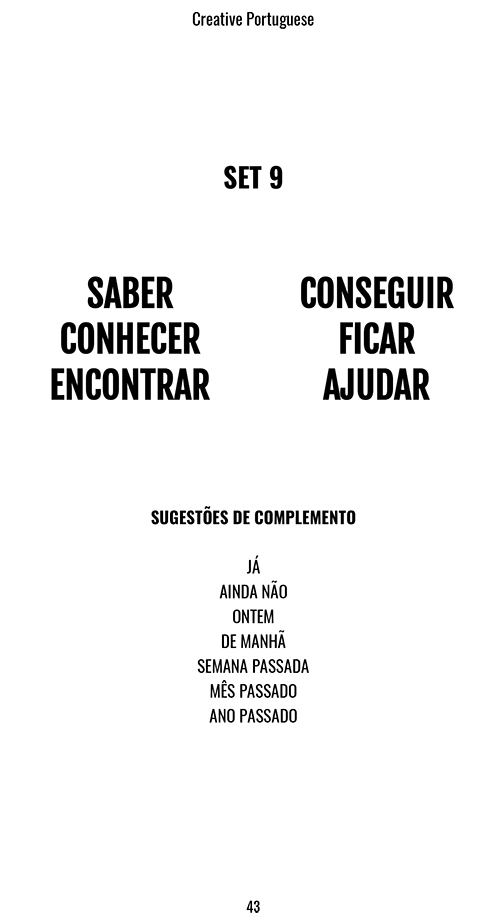

There are 18 sets in the book. Enough to become fluent in the language, as long as you master each set. Let’s see an example:

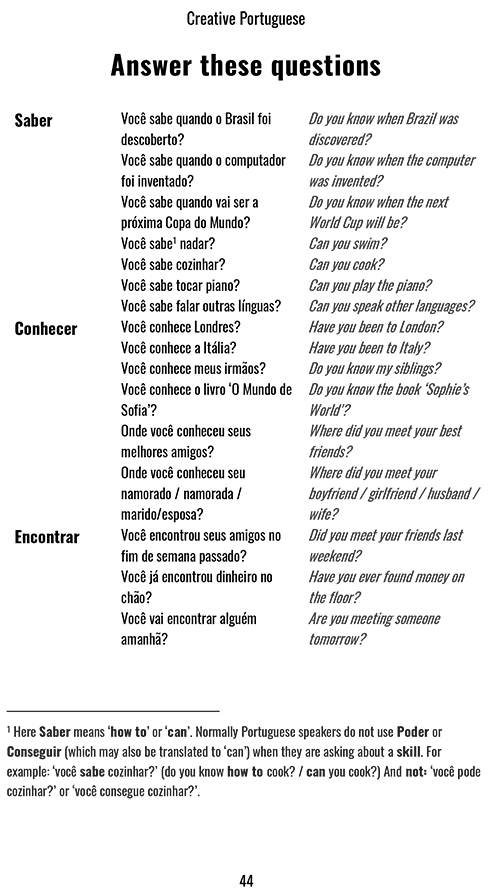

Above we have SET 9. In this set the student will be practising Saber (to know), Conhecer (to know, to meet), Encontrar (to meet, to find), Conseguir (to be able to), Ficar (to stay, to become, to be situated), Ajudar (to help). The tense focus are Present and Past (PPS) and at this stage the student is already working with irregular verbs. The idea is that the student will learn how to use each one of these verbs and the proposed tense conjugations. As soon as he ‘masters it’, he can move on to the next set. Have a look at some questions related to this set:

The last few sets, set 16, set 17 and set 18 are theme related. So for example, SET 18 is about Posse e Propriedade (Ownership and Property). The verbs are Emprestar (to lend), Devolver (to return/to give back), Alugar (to rent, to hire), Reservar (to reserve, to book), Trocar (to change, to exchange), Vender (to sell). You can see how these verbs are related. Learning them through asking and answering questions is a great way for transforming the learning experience into a real life experience.

Finally, I just would like to point out that this book can be used for learning Brazilian and European Portuguese. Many times when I taught group classes, the language school I used to work for asked the students to buy the book in a single dialect (not their fault, as there are no many options for mixed dialects!). So sometimes we had European Portuguese books, but half of the students were learning Brazilian Portuguese. This was really frustrating as there are so many differences! This new method is the perfect option for mixed dialect classes.

In future I’m hoping to translate the method to be used for learning other languages as well.

12/06/2018 UPDATE: Now a version of this book for learning Italian has been published. Same method. The title is: “Creative Italian, Learn through speaking”. Check it on: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/199974974X/

Creative Portuguese is available on Amazon:

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Brazil: https://www.amazon.com.br/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

France: https://www.amazon.fr/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Italy: https://www.amazon.it/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Germany: https://www.amazon.de/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Spain: https://www.amazon.es/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Japan: https://www.amazon.co.jp/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

US and rest of the world: https://www.amazon.com/Creative-Portuguese-Learn-through-speaking/dp/1999749731/

Posted on January 17, 2017

Será que… I wonder if…

In spoken language, not everything can be easily translated from English to Portuguese and vice-versa. There are many words and expressions that complicate the life of translators and interpreters. In English we have the sentence: “I wonder if…” Usually translators will translate this as “Eu me pergunto por que…”. But that’s not very correct, people never say this in colloquial Portuguese. However, there is a similar expression in Portuguese: “Será que…?”, which literally means “Will it…?”. For example:

In spoken language, not everything can be easily translated from English to Portuguese and vice-versa. There are many words and expressions that complicate the life of translators and interpreters. In English we have the sentence: “I wonder if…” Usually translators will translate this as “Eu me pergunto por que…”. But that’s not very correct, people never say this in colloquial Portuguese. However, there is a similar expression in Portuguese: “Será que…?”, which literally means “Will it…?”. For example:

- Será que vai chover hoje? = I wonder if it will rain today.

- Será que ele vem? = I wonder if he will come.

If the first example was translated to “Eu me pergunto se vai chover hoje” it would be comprehensible, but it wouldn’t sound natural at all. The same for the literal translation to English “Will it rain today?”… It doesn’t express the same kind of doubtful meaning. I’ve seen many translations like this because it’s a very common mistake made by translators and translation tools such as Google Translate (see the article When Google Translate Fails…).

However, it’s important to note that there are other similar cases with the verb ‘to wonder’. Above we have analysed ‘wonder if‘. If we take ‘wonder why‘ or ‘no wonder‘, then we have other meanings to translate. From English to Portuguese:

- I wonder why he didn’t come = Eu queria saber por que ele não veio.

- You may wonder why he didn’t come. = Você deve estar querendo saber por que ele não veio.

- No wonder he didn’t come = Não me supreende que ele não tenha vindo.

In these cases, many translators also continue to use the verb ‘perguntar’ in its reciprocal form (for example: “Eu me pergunto por que ele não veio”). Sometimes, depending on the context, it’s fine, but in general, they are bad translations.

I wonder if this article will help translators to improve their translations quality in future. (Será que este artigo vai ajudar os tradutores a melhorarem a qualidade de suas traduções no futuro?)

Posted on April 13, 2016

Advice for Teaching Foreign Languages

I’ve been teaching Portuguese as a foreign language for nearly 10 years now, and I must say that my techniques and lesson plans have changed a lot comparing to the days when I didn’t have much experience. Teaching experience makes a huge difference! I have realised that many language teachers do this as a hobby or as a second job, and won’t bother providing a good learning environment to their students. In my case, I made it a business and from part-time it became a full-time job, so I had to dedicate much of my time developing an approach to teach language and strategies to train the mind for language purposes. In this post I will be sharing some of my personal thoughts on teaching foreign languages.

I’ve been teaching Portuguese as a foreign language for nearly 10 years now, and I must say that my techniques and lesson plans have changed a lot comparing to the days when I didn’t have much experience. Teaching experience makes a huge difference! I have realised that many language teachers do this as a hobby or as a second job, and won’t bother providing a good learning environment to their students. In my case, I made it a business and from part-time it became a full-time job, so I had to dedicate much of my time developing an approach to teach language and strategies to train the mind for language purposes. In this post I will be sharing some of my personal thoughts on teaching foreign languages.

5 Fundamental Concepts for Teaching Foreign Languages

1. Greeting Habits: Every time you see your students you need to repeat basic things in a natural way, such as saying greetings (hello, good morning, how are you?, etc.) in the target language, of course. It’s necessary to do this every single lesson using the same content, until they are ready to learn new greetings.

2. Conversational Habits: When students are not completely beginners and can manage to use the past, present and future tenses, I introduced questions about their lives. That’s how I always start my lessons, asking between 4 to 10 questions such as: “what did you do today/yesterday/at the weekend?”,”what will you do after the class/tomorrow/this weekend?”, “anything new?”, “any questions?”, “are you hungry/thirsty/tired?”, “what day is today?” etc.

3. Make them active learners: There are many different types of students, while some are more passive others are more active. Active students will ask questions and show interest. Those are the ones who will succeed faster. Some people are more reserved. They answer the questions but they don’t come up with their own. If the students are passive, encourage them to ask questions about you. Help them to develop this habit. In addition, asking the students what they want to learn is also helpful. Encourage them to be independent learners.

4. Interest and Attention: Reading and conversation topics must be interesting to the student, as well as to the teacher. If only one person is showing interest, there will be a lack of joint attention. Joint attention (read on Wikipedia) is critical for learning development. For example, if the teacher and the student are working together together on a text and something funny comes up, the teacher may laugh. Consequently the student will make an association with that word or particular scenario which will help him memorising things.

5. Provide Associations: Experienced teachers will know the vocabulary that students struggle to memorise. There are verbs that my students forget, such as the verb esquecer, which, funny enough, means “to forget”. Then I always say: você esqueceu o verbo “esquecer”! (you forgot the verb “to forget!”). Then I suggest they think the verb has “escaped” from their minds, because the initial sound is the same (ESCA(PE)…ESQUE(CER)…). So the information “escapes” when you forget. This is one of many other examples of associations that a teacher must know and use in class.

Questions that Teachers have about Teaching Languages

1. Do you let your students recall vocabulary by themselves?

1. Do you let your students recall vocabulary by themselves?

For example, the student is telling you a story and then suddenly he gets stuck, he doesn’t remember the verb “to bring”. He says: “I’m trying to remember the verb ‘to bring’…” Do you wait for him?

There are a few options for this situation:

a) Wait.

b) Tell him to look on a dictionary.

c) Give him the answer straight away.

d) Help him to remember with some clues.

Some teachers would always choose the same option. I think this is a bad habit because it will depend on the circumstances. However, the teacher shouldn’t waste time and evaluate this fast. First, it’s necessary to know your student well. If he has said this same word in the past and is just suffering a short lapse of memory (like the tip of the tongue phenomenon > see on Wikipedia), then you can help him to remember it, with associations or giving him the first letters. You can also give him the answer straight away, saving time and letting him to continue with his story. Second, you need to know the importance of the word and the relevance of this word for his vocabulary. In this case, tell him to look on a dictionary because this creates a good habit and helps with memorisation. If he shows signs of desire to recall the word, just wait. But don’t wait too long, if he is taking more than 15 seconds, it’s likely he will not remember and may become frustrated. Before this happens, give him some clues.

2. Do you correct your student every single time?

Imagine your student says something comprehensible, but using the wrong conjugation. Do you let it pass? In some cases I don’t, correcting the student. The teacher must be careful so the student doesn’t create a bad habit. But in other cases, it’s better not to break the flow. When students say a whole sentence and are understood without interruptions, they gain confidence.

3. Should you speak the target language all the time? Are you allowed to speak English during the lessons?

In some language schools that I have worked they demand that teachers speak only the target language for the whole duration of the lesson. I understand why, but in some cases this is not feasible. If you are teaching completely beginners, they may feel lost for the whole lesson and not learn a single thing. The way adults learn a foreign language is not the same as children learn their mother tongue. Also, students may not know anything about you and no bond will be created between the teacher and the student, which is something very important. But certainly, English (or any other fluent language between teacher/student) must be avoided as much as possible and students must be motivated all the time to try to use the target language.

4. If something is hard to explain, do you allow your students to speak English?

Sometimes I do. I don’t like when students book a lesson with me on the wrong date because of a language misunderstanding (Quinta-feira is Thursday, not Tuesday!). And there are cases where students are tired, their brains will not work non-stop in a foreign language, so they need a break. When I give a 2 hours lesson, I already expect a few breaks to talk about other things in English. But if the student is in an advanced level and the lesson is not that long, I motivate them to speak Portuguese and I help them with the challenge.

As you could see here, teaching a foreign language is not a very easy task. Some people may think any native of the target language can teach, but this is not true. A native speaker doesn’t replace the teacher. To teach a language is necessary to have patience, to be willing to support the student’s learning as well as to understand grammar and learning strategies.

Posted on January 19, 2016

Para vs Por

When we translate English to Portuguese and vice-versa, sometimes the prepositions “para” and “por” will have distinct translations. Usually it works like this:

1) Basic Use:

Para = To

Por = For

Examples:

a) Eu vou para o supermercado. = I’m going to the supermarket.

Here “para” is used to indicate a destination.

b) Eu vou ficar aqui por 2 dias. = I will stay here for 2 days.

Here “por” is used to indicate duration.

But that is not entirely true. In some cases “para” becomes “for”!

2) Common cases when “para” becomes “for”:

a) Eu preciso comprar vinho para o jantar = I need to buy wine for dinner.

b) Escolas são para aprender. = Schools are for learning.

In these two cases para means “for the purpose of”.

c) 1. Este presente é para você / 2. Este presente é para o seu amigo.

= 1. This gift is for you. (as showing the intention of offering something)

2. This gift is to your friend (as just showing something, not offering)

In English there is a difference between using “for” and “to”: “for” implies the intention of offering something. However, in Portuguese “para” is used in the two examples above. Only in a few cases “intention” is expressed with the preposition “por”, usually when the sentence means “for someone’s sake”, such as: “Eu vivo por você = I live for you (for your sake)”. There is a well-known Brazilian song called Por Você (which, by the way, is great for practising the conditional tense).

Other misleading translations come from idiomatic cases.

3) Portuguese idiomatic cases:

a) Por aqui. = Around here. / By this way.

b) Por último. = Finally.

c) Por fim. = Ultimately. / Lastly.

d) Por engano = By mistake.

4) English idiomatic cases:

a) I’m going for a walk. = Eu vou passear. (Literal: I’m going to take a stroll)

b) I’m going for a beer. = Eu vou beber uma cerveja. (Literal: I’m going to drink a beer)

5) Other translations for “para”:

a) Eu preciso disso para segunda-feira. = I need this by Monday.

b) Eu estou para sair. = I am about to leave.

In case you were wondering about the book title (image) in the beginning of this post, here is the translation:

Image Translation: Um presente para você, porque uma pessoa que lê vale por duas.

= A present for you, because a person who reads is worth two.

In this case “por” is omitted in English.

If you are learning Portuguese, I believe the best way of memorizing these rules is repeating the same sentences over and over. You can practise using all the examples found in this article:

1. Eu vou para o supermercado.

2. Eu vou ficar aqui por 2 dias.

3. Eu preciso comprar vinho para o jantar.

4. Escolas são para aprender.

5. Este presente é para você.

6. Este presente é para o seu amigo.

7. Por aqui.

8. Por último.

9. Por fim.

10. Por engano.

11. Eu preciso disso para segunda-feira.

12. Eu estou para sair.

If you want to learn more about the use of “para” (indicating a destination), see this post:

Saying “To” in Portuguese (Ao, Para o, Pro, No)?